The world of folk medicine is a living tapestry woven from generations of knowledge, rituals, and botanical wisdom. At its heart lies a profound connection to the land and its native plants, a relationship that has shaped healing practices for millennia. Today, as we turn to herbal remedies for wellness, we are often unwittingly drawing from traditions that stretch back to the ancient Celts and Germanic tribes. Remarkably, nearly half of the plant species still used in modern herbal medicine were already recognized and utilized by these early European peoples, highlighting the enduring legacy of their healing heritage.

The story of the Celts and Germanic peoples is deeply rooted in the sweeping migrations of the ancient Indo-European tribes, whose legacy continues to shape the languages, cultures, and traditions of much of Europe and parts of Asia. Both Celts and Germanic peoples are members of the vast Indo-European (sometimes called Indo-Germanic) family, a group whose origins trace back to the so-called “Kurgan people”, pastoralists who lived on the southern Russian steppe along the lower Volga River during the Stone Age.

Origins: The Kurgan People and Their World

Archaeologists have given the name “Kurgan” to these early pastoralists, derived from the Russian word for their distinctive burial mounds. These kurgans are not just simple graves; they are complex monuments, often containing chambers filled with grave goods and sometimes even horses and chariots, reflecting a society that honored its dead with elaborate rituals and offerings. The Kurgan culture, as described by scholars like Marija Gimbutas, was marked by a nomadic lifestyle, with a reliance on herding and a deep connection to the land and its cycles.

The Kurgan people are widely regarded as the original speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, the mother tongue from which all Indo-European languages, including those of the Celts, Germanic tribes, Greeks, Romans, and many others, descend. Their homeland, the Pontic-Caspian steppe, was a vast grassland stretching from the lower Volga to the northern shores of the Black Sea, a region that shaped their way of life and, ultimately, their destiny.

Migration and Change

Around 2000 BCE, a combination of factors, overpopulation, the overuse of pastures, and significant climatic changes, triggered a series of migrations that would change the face of Eurasia. The Kurgan people, already skilled in animal husbandry, had tamed the horse and developed wagons, innovations that gave them a decisive advantage in mobility and transportation. With these technologies, they could move large groups of people, livestock, and goods over long distances, enabling them to expand rapidly into new territories.

The migrations unfolded in several directions: some tribes moved westward into Europe, where they would become the ancestors of the Celts, Germanic peoples, and others; others traveled southward into Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and Greece, while still others ventured eastward toward Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. These movements were not always peaceful, but they were transformative, bringing new languages, technologies, and cultural practices to the regions they entered.

The Legacy of the Kurgan Migrations

The arrival of Indo-European tribes in Europe, Anatolia, and beyond marked the beginning of a new era. In Anatolia, for example, the Hittites established one of the great empires of the Bronze Age, while in Greece, the Mycenaeans laid the foundations for classical Greek civilization. In Europe, the descendants of these migrants, the Celts and Germanic peoples, developed rich and distinctive cultures, each shaped by their environment and history, but united by their shared Indo-European heritage.

The influence of the Kurgan people can still be felt today. Their linguistic legacy is evident in the family of Indo-European languages, which includes most of the languages spoken in Europe, as well as many in South Asia and the Middle East. Their technological innovations, especially the domestication of the horse and the invention of the wheel and wagon, revolutionized transportation and warfare, enabling the rapid spread of peoples and ideas across vast distances.

The Celts, whose culture flourished across Central and Western Europe from around 800 BC to 500 AD, developed a sophisticated system of medicine that was deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs and natural environment. Their approach to health was holistic, emphasizing the balance between mind, body, and spirit. Central to Celtic healing were the druids and wise women, who combined herbal remedies with charms and incantations, believing that the potency of a plant could be enhanced by ritual and intent. The Celts’ extensive knowledge of local flora allowed them to treat a wide array of ailments, from fevers and infections to wounds and chronic pain. Plants such as foxglove, self-heal, burdock, and yarrow were staples of their pharmacopeia, many of which remain in use today. Celtic medicine was not merely practical; it was also deeply symbolic, with certain plants believed to ward off evil spirits or bring good fortune.

Similarly, the Germanic tribes, who inhabited the forests and valleys of northern Europe, cultivated a rich tradition of natural healing that prioritized harmony with nature and community. Their practices, known collectively as Kräuterheilkunde (herbal medicine), were passed down through generations and refined by monastic communities during the Middle Ages. Monks and nuns maintained herb gardens and compiled manuscripts detailing the uses of plants like chamomile, St. John’s wort, peppermint, and valerian, herbs that are still popular in contemporary herbalism. The Germanic approach, much like the Celtic, was holistic, viewing health as a reflection of one’s relationship with the natural world and the broader community.

The overlap between Celtic and Germanic herbal traditions is significant. Both cultures valued the wisdom of oral tradition, the importance of community in healing, and the spiritual dimension of medicine. They shared many of the same plants, yarrow, chamomile, nettle, and plantain, to name a few, and employed similar methods of preparation, such as infusions, poultices, and ointments. These shared practices suggest a common cultural and ecological heritage, with knowledge exchanged through trade, migration, and intermarriage.

The Celts hold a distinguished place in European history as the first people to usher in the widespread use of iron across the continent. Often referred to as Europe’s first “iron people,” the Celts revolutionized technology and daily life by forging iron into practical tools and weapons. They were pioneers in crafting scythes, vast improvements over earlier bronze sickles, as well as ploughshares, chariot wheel tires, and a variety of weapons. While bronze had already accelerated work and productivity, iron’s superior durability and sharpness brought about an even greater leap forward, enabling more efficient farming and greater production surpluses. This technological advantage not only made life easier but also allowed communities to trade goods beyond mere subsistence, fostering economic growth and cultural exchange.

Among the Celtic tribes, the Helvetii, originally shepherd clans, adapted to new environments by settling in the Alpine regions. Over time, these clans evolved into Alpine dwellers, establishing themselves in higher valleys and even crossing mountain passes once considered impassable. The ancient migration routes that had brought their ancestors from the Black Sea region, along the Danube and into Central and Western Europe, now became vital trade arteries connecting the Celtic world with distant lands to the east.

This network of trade routes not only facilitated the movement of goods but also the exchange of ideas and botanical knowledge. Foreign plants such as the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), lentil (Lens esculenta), pea (Pisum sativum), and broad bean (Vicia faba) were introduced to new regions, whether carried intentionally as cultivated crops by migrating groups or acquired through trade. These introductions enriched local diets and agricultural practices, further integrating the Celts into a broader Eurasian cultural and economic sphere.

The great migration of Germanic tribes from northern Europe toward the south began in earnest during the 5th century AD, marking a pivotal chapter in European history. These migrations were part of a much longer movement: centuries earlier, ancestors of the Germanic peoples had journeyed from the southern Russian steppes, following river routes northward to settle in the Baltic and North Sea regions, including Scandinavia.

By the 5th century, the pressure of new arrivals and changing conditions prompted a southward shift. Among the most influential tribes were the Alemanni, who overwhelmed Roman defenses along the Rhine and surged into northern and central Switzerland. Meanwhile, the Burgundians moved into western Switzerland, where they intermingled with the remaining Celtic populations, blending cultures and traditions.

The migrations did not end with the collapse of Roman rule. In the 8th and 9th centuries, Alemanni tribes pushed further, crossing formidable Alpine passes such as the Grimsel, Lötschen, and Gemmi, and entered the rugged landscapes of Valais. Here, they encountered the Celtoromanic inhabitants, descendants of the earlier Celtic and Romanized populations, leading to tensions and conflict. Over time, the Alemanni gradually asserted themselves, while the Celtoromanic people retreated into the more remote side valleys and higher elevations of Upper Valais, where they adapted to the demanding environment as mountain farmers and livestock breeders.

Folkloristic studies of the Walser people, who settled in regions such as the Lötschental, Upper Valais, Urseren Valley, and Graubünden, provide compelling evidence of this Alemannic heritage. The mountain communities relied on the rich biodiversity of their surroundings, utilizing montane and alpine species of medicinal herbs that had long been familiar to their ancestors. This tradition of herbal knowledge, passed down through generations, underscores the enduring legacy of the Germanic migrations and their profound impact on the cultural and ecological landscape of the Alps.

For both the Celts and the Germanic tribes, the sun was revered as the life-giving source of light and energy, vital for all living things. The daily cycle of sunrise and sunset not only marked the passage of time but also symbolized the alternating rule of the gods of light and the darker, more mysterious forces that governed the night. During the day, benevolent deities associated with light were believed to hold sway, while at night, evil or chaotic powers were thought to emerge.

Among the most significant events of the year were the solstices, the summer solstice (around June 21) and the winter solstice (around December 23). These turning points in the solar cycle were celebrated with special rituals and festivities, as they marked the longest and shortest days of the year, respectively. The solstices were believed to be moments of heightened spiritual power, when the boundary between the human and divine worlds became especially thin.

Equally important were the equinoxes, the spring equinox (around March 21) and the autumn equinox (around September 23), which heralded the beginning of spring and autumn. These dates were closely observed, not only because they signaled important agricultural transitions, but also because they were often accompanied by dramatic and sometimes frightening storms. The Celts and Germanic tribes interpreted these tempestuous periods as moments when the natural and supernatural worlds interacted most intensely, and they marked the occasions with rituals aimed at protecting their communities and ensuring a fruitful year ahead.

Christianity’s Adoption of Pagan Traditions

Christianity, when spreading across Europe, often absorbed and repurposed deeply rooted pagan festivals and customs, recognizing their importance in the lives of the people. Many Christian holidays today still echo ancient celebrations of nature’s cycles, fertility, and protection.

Easter and the Goddess of Spring

The name “Easter” itself is believed to derive from “Ostara,” a Germanic goddess of spring and dawn, symbolizing renewal and rebirth. The festival’s timing, coinciding with the awakening of nature, was already significant in pre-Christian times.

Maundy Thursday and the Legacy of Donar

Maundy Thursday retains traces of the Donar (Thor) cult, especially in spring rituals. Traditionally, cabbage, sometimes called “haidnischkol” (heathen cabbage), was eaten with nine spring herbs. This dish, cultivated and preserved for ritual use, was believed to bring health and protection.

Ascension and Herbal Power

The Christian feast of the Ascension of Christ is also celebrated on a day once dedicated to Donar. Herbs gathered on this occasion were considered especially potent for medicinal use, a tradition reflecting the blending of pagan and Christian beliefs.

Pentecost: From Fertility Rites to Christian Festival

When the elder bush began to bloom, Indo-Europeans celebrated the start of summer with fertility festivals. Over time, these evolved into Pentecost. The custom of decorating sacrificial animals, originally involving human sacrifice, was replaced by the Pentecost oxen. Celtic tradition saw animals garlanded with vervain (Verbena officinalis), wormwood (Artemisia spp.), and St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum).

St. John’s Day: The Christianized Summer Solstice

The Feast of St. John, celebrated around the summer solstice, has roots in sun worship. The lighting of fires, a central ritual, was believed to purify and protect. Before sunrise, nine medicinal herbs were collected and woven into a “St. John’s bush,” which was passed through the smoke of the fire and kept for a year as a talisman against evil and illness. Fire and smoke were seen as magical purifiers.

Notable St. John’s Herbs

- St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): Known as “harthew,” “fuga demonum,” and “sola regia,” this plant’s many names attest to its importance. Used by Germanic tribes to garland sacrificial animals, its yellow flowers symbolized death. Today, it remains a popular remedy for wounds.

- Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris): Called “biboz” in Old High German and “mugwurtz” in Celtic (“mic-glo,” meaning to warm), it was used as a worm remedy and to protect against malicious spells during childbirth.

- Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare): Known as “reinefano” (Germanic) and “arwaz” (Breton), it was mainly used as an abortifacient.

The St. John’s Belt and Apotropaic Plants

The “Sonnwendgürtel” (summer solstice belt), Christianized as the “Johannisgürtel,” was worn around the waist on St. John’s Day and thrown into the fire in the evening, symbolizing the release of the past year’s burdens. These belts were made from plants like lycopodium (Lycopodium spp.), mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris), and ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea), known in French as “courroie de Saint-Jean.”

Most apotropaic (magic-repelling) plants were once components of sacrificial offerings, woven into wreaths and garlands to decorate animals, sacred trees, and graves. This tradition may also explain the origin of “thunder herbs,” dedicated to Donar (Thor) and used to protect against lightning:

- Thunder vine: Goutweed (Glechoma hederacea)

- Thunder beard: Houseleek (Sempervivum tectorum)

- Thunder broom: Mistletoe (Viscum album) and broom (Cytisus scoparius)

- Thunder herb: Water eupatorium (Eupatorium carmabinum)

- Thunder nettle: Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

- Thunder thistle: Eryngium or Carlina

Christmas: The Holy Nights of Winter

Christmas coincides with the “Wihinächte,” the holy nights of the winter solstice, a time of darkness and storms, when evil spirits and gods of darkness were invoked. The famous Celtic druidic ritual of harvesting mistletoe, best collected in winter, takes place during this period. Mistletoe, along with holly (Ilex aquifolium), became symbols of luck and protection in once-Celtic lands like England, Ireland, and Scotland, and remain beloved Christmas decorations today.

In the Celtic priestly caste of the druids, the ovates held the second highest rank. They conducted sacrificial rites and fulfilled the roles of seers and healers. Their extensive knowledge of nature and medicine was passed down to their disciples through oral traditions, often in the form of didactic poems.

Women were also present among the druids and ovates, playing significant roles within the order. It was only after the conversion to Christianity that some of these women began to record their knowledge in writing. By this time, under Roman rule, they were already acquainted with the medical writings of Greek and Roman physicians, which further enriched their practices.

Among the Germanic tribes, it was chiefly women known as “wise women” or “whales” (a term still echoed in the French “sages-femmes,” meaning midwives) who practiced the art of healing. These women not only cared for the sick but also served as seers, exerting considerable influence over the fate and wellbeing of their communities. Their wisdom and skills made them indispensable figures in the spiritual and everyday life of their tribes.

Both the Celtic and Germanic peoples maintained medicinal plant beds near their homes, often referred to by the Old High German term “lubigortos”, where “lubi” means “poison.” These gardens demonstrated a deep knowledge of both healing and poisonous plants, which they carefully cultivated and used for various purposes. In addition to medicinal species, they grew food plants as well as some fiber and dye plants, creating diverse herb gardens that supported both daily life and specialized crafts.

Archaeological evidence from grave goods, such as dried fruits, nuts, roots, and even seeds of useful plants, provides insight into their diets and horticultural practices. The inclusion of these provisions with the dead suggests they were intended as sustenance for the afterlife. Furthermore, the discovery of medicinal herbs and seeds among burial offerings clearly indicates the importance of gardening in their culture. These burial gifts were not only practical but also symbolic, ensuring that the deceased could continue to cultivate and benefit from plants even in the next world.

Both the Celts and the Germanic tribes carefully observed the cycles of the moon to guide all their agricultural activities, such as sowing, planting, gathering, harvesting, and even felling trees. They revered the moon as a powerful deity, believing it sent the nourishing dew and exerted a profound influence over all aspects of life: growth, death, and the cycle of rebirth. In their worldview, the moon’s phases were essential for ensuring the fertility of the land and the success of their crops.

In the Indo-European herb garden grew, among other things:

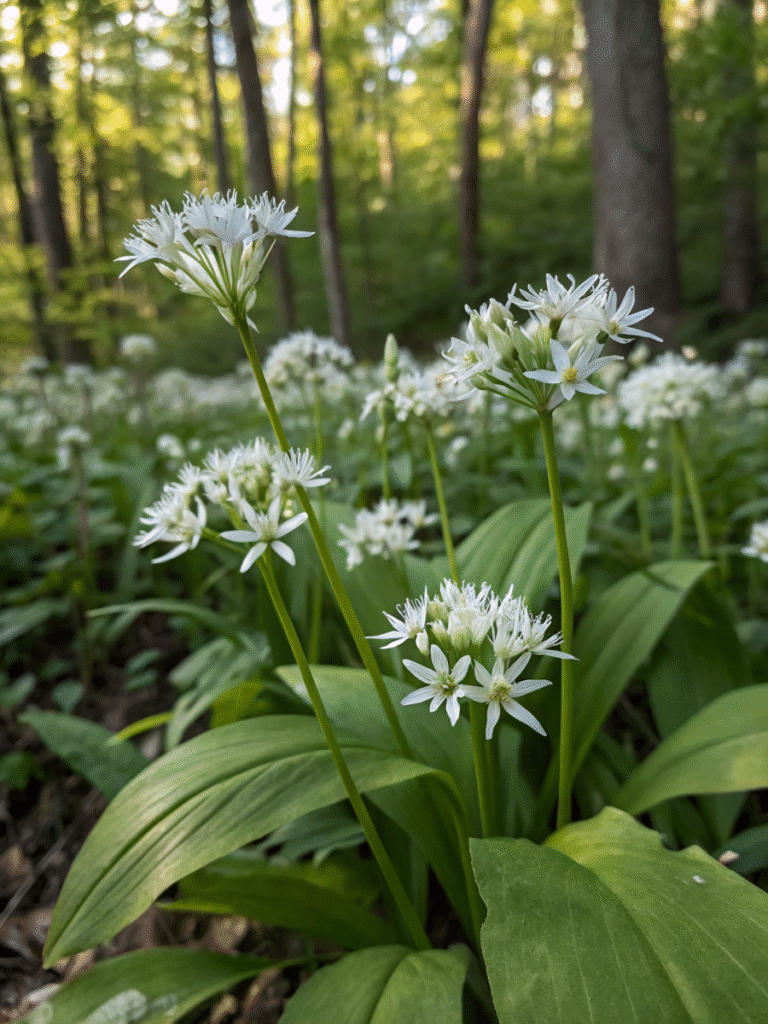

Wild garlic (Allium ursinum), known in Old High German as “rams” or “ramser” during the early Middle Ages and called “kramo” in Celtic, is among the oldest cultivated food plants in garden history. As one of the classic spring herbs, it was deeply valued for its culinary and medicinal uses. Its connection to the bear, evident in its Latin species name ursinum, highlights its significance as a Germanic “soul animal” or totem, symbolizing strength and renewal.

Interestingly, leek species in general were held in high regard by both the Germanic tribes and the Greeks, who believed they could enhance martial courage. This association may also help explain the symbolic link between wild garlic and the bear, as both were seen as powerful, protective forces. The bear’s legendary might and the leek’s reputed ability to inspire bravery may have intertwined in the cultural imagination, further elevating the status of wild garlic in ancient traditions.

Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), known as “rosshueb” in some regions, “callio-marcus” in Gaelic-Celtic, and “pav-marc’h” in Breton-Celtic, has a long history as a trusted remedy among the Celts. Traditionally used to soothe coughs, the plant was dried and burned, with the resulting smoke inhaled through a reed to provide respiratory relief. Both the Celts and the Germanic tribes also valued coltsfoot for its healing properties, often applying fresh leaves directly to wounds to promote recovery. This versatile herb thus played a dual role in early European medicine, serving as both a respiratory aid and a wound dressing.

t.b.c.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.