Deep beneath the mist-shrouded peaks of the Black Forest, where ancient pines whisper secrets to the wind and legends of witches and wanderers linger in the shadows, lies a hidden vault that safeguards the very soul of a nation. Tucked into the rugged flanks of the Schauinsland mountain near Freiburg im Breisgau, the Barbarastollen, or Saint Barbara Tunnel, stands as an enigmatic testament to Germany’s enduring reverence for its cultural legacy. This disused mining tunnel, transformed into a fortress of memory, holds the microfilmed essence of centuries of history, art, and literature, protected from the perils of war, catastrophe, or time itself. For those fascinated by German culture, the Barbarastollen is more than a repository; it is a subterranean sanctuary that embodies the resilience of a people who have learned, through the scars of the twentieth century, the irreplaceable value of their heritage.

The story of the Barbarastollen begins not with grand architectural designs or scholarly decrees. Miners clawed at the silver veins deep in the Black Forest, their picks echoing like thunder in the damp earth. Sweat stung their eyes. Dust choked the air. In 1903, they began carving the Barbarastollen, a narrow horizontal tunnel to haul ore and supplies from the Schauinsland mines to a railway station in the misty Hintertal valley. They pushed forward just 700 meters. Then, money dried up. Rock walls buckled under unexpected twists. The work halted. The tunnel lay forgotten, its mouth choked by tangled vines and fallen leaves, as decades blurred into silence.

The Cold War’s chill winds revived it in the early 1970s. Sirens wailed in distant cities. Bomb shelters sprouted like mushrooms. West Germany hunted for a hidden vault to shield its treasures: ancient scrolls, priceless paintings, fragile manuscripts. No cities nearby. No army bases. Just the Schwarzwald’s thick pines whispering secrets, and the Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald’s rugged hills standing guard. Deep beneath layers of jagged gneiss and granite, the nation could tuck away its past, safe from the mushroom clouds that haunted nightmares.

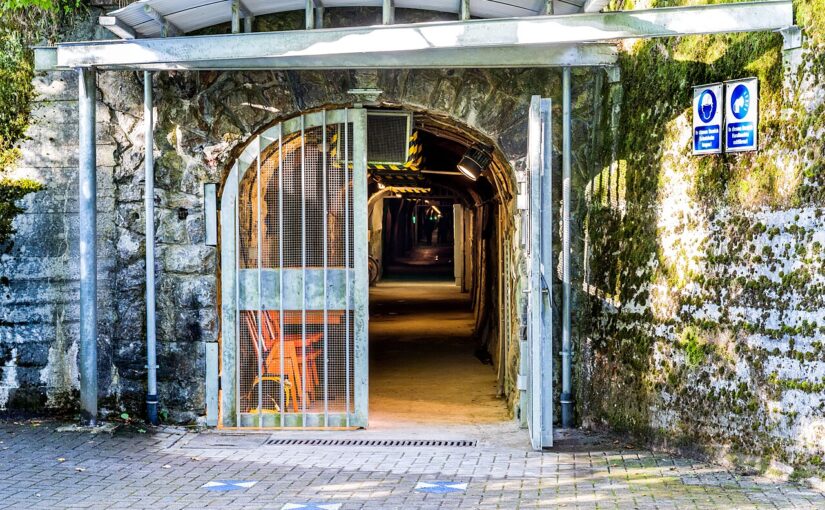

By 1972, engineers and archivists set to work converting the forgotten stollen into the Zentrale Bergungsort der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, the Central Storage Site of the Federal Republic of Germany, under the auspices of the Bundesarchiv (Federal Archives). The transformation was methodical and unyielding: the main tunnel, stretching 680 meters into the mountain’s heart, was reinforced with sprayed concrete for structural integrity, while two lateral side tunnels, each 50 meters long, were carved as dedicated storage galleries branching off midway. Pressure-tight steel doors were installed at the entrance, capable of withstanding explosions or floods, and the entire complex was buried beneath 400 meters of solid rock to shield it from seismic shocks, meteor strikes, or atomic blasts. Remarkably, the natural conditions within the Barbarastollen provide ideal preservation without modern interventions; the temperature hovers steadily at around 10 degrees Celsius (with a mere two-degree variance), and humidity remains at a consistent 70 percent, mimicking the controlled environments of the world’s finest museums. The first microfilm deposits arrived in 1974, and by April 24, 1978, the site earned a rare distinction: registration with UNESCO as the sole German facility under special protection by the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. This places it among only five such global sanctuaries, with the others located in the Vatican and the Netherlands. Each is marked by a distinctive emblem of three ultramarine-blue shields on a white field, a symbol of humanity’s collective vow to shield culture from destruction.

At the core of the Barbarastollen’s mission is its role as a bulwark against loss, a direct response to the horrors of World War II, when Nazi zealots burned books, looted art, and razed libraries in a frenzy of ideological erasure. The convention that protects it, signed by over 130 nations in 1954, arose from this devastation, affirming that “damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all mankind.” In the tunnel’s dim, vaulted chambers, over 1,400 stainless-steel containers, each hermetically sealed at 35 percent humidity to ensure longevity, house more than 32,000 kilometers of 35-millimeter polyester microfilm that capture approximately 1.12 billion images from archives, museums, and libraries across Germany. These are not mere backups but facsimiles of irreplaceable originals, etched in black-and-white (and, since 2010, color) to endure for at least 500 years without degradation. Among the treasures preserved here are the treaty text of the Peace of Westphalia from 1648, which reshaped Europe’s map after the Thirty Years’ War; the papal bull issued by Pope Leo X in 1520, excommunicating Martin Luther and igniting the Protestant Reformation; the coronation document of Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor, from 962; personal papers of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Enlightenment’s literary giant; and the original building plans for the Cologne Cathedral, that Gothic marvel whose spires pierce the Rhineland sky. More modern relics include the Grundgesetz, Germany’s Basic Law of 1949, which the site’s 2,165th barrel commemorated as its one-billionth document in 2016. Even artifacts from the former German Democratic Republic, deposited after reunification in 1990, find refuge here, bridging the divides of a fractured past.

The engineering feats behind the Barbarastollen’s preservation are as ingenious as they are understated, reflecting the German tradition of Präzision, or precision, in craftsmanship. Access is rigorously controlled: no military vehicles may approach within three kilometers, the airspace overhead is a no-fly zone, and only two security personnel hold the code to the armored entrance door, monitored by motion sensors and CCTV. Movement within is by electric cart along the smooth concrete floor, past rows of gleaming barrels stacked to waist height in the side galleries. The microfilms, wound onto reels and encased in corrosion-resistant steel, are designed to withstand not just time but the elements; should a disaster strike the surface, these duplicates could be retrieved and reprinted to rebuild shattered collections. This foresight proved vital in 2009, when the Historical Archives of the City of Cologne collapsed in a tragic flood, destroying 90 percent of its holdings. The surviving million photographs were swiftly transferred to the Barbarastollen, underscoring its practical role beyond mere symbolism. Today, the archive continues to grow at a rate of 1.5 million documents annually, adapting to digital threats by incorporating scanned records while relying on the timeless reliability of film over fleeting electronic media.

Yet the Barbarastollen’s true significance transcends steel and stone; it is a profound cultural emblem of Germany’s Verpflichtung, or commitment, to preserving the threads that weave its identity. In a nation where history is not distant folklore but a living dialogue, as seen in the passionate debates over Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe or the restoration of Dresden’s Frauenkirche, this underground haven symbolizes a collective atonement for past losses and a pledge against future ones. It honors the intellectual giants like Luther and Goethe, whose words shaped European thought, and the architects whose visions endure in stone and script. By safeguarding these elements, the Federal Archives ensure that the richness of Germanic traditions, from the sagas of the Holy Roman Empire to the philosophical depths of the Enlightenment, remains accessible, fostering education and reflection in an era of rapid change. The tunnel’s namesake, Saint Barbara (Heilige Barbara), adds a layer of poignant folklore. Revered since the third century as the patron saint of miners and all who face sudden peril such as lightning, explosions, or untimely death, her legend of imprisonment in a tower by her pagan father mirrors the site’s own seclusion. Miners in the Black Forest, much like their medieval counterparts, invoked her protection with prayers and feasts on December 4, blending Christian piety with the raw dangers of the earth. In naming the stollen after her, Germany invokes this heritage, transforming a miners’ refuge into a broader shield for cultural survival.

As one ventures deeper into the Barbarastollen’s lore, it becomes clear how such a place bridges the chasm between eras, allowing the echoes of the past to resonate in the present. Imagine the quiet hum of the ventilation system, the faint scent of cool stone, and the weight of history pressing from all sides; here, in this man-made cavern, the Reformation’s fire, the Empire’s glory, and the Republic’s fragile peace coexist in miniature form, immune to the frailties above. For future generations, the Barbarastollen matters profoundly: in a world beset by climate crises, geopolitical tensions, and digital ephemera, it reminds us that true endurance lies not in invincibility but in deliberate care. By investing in such fortresses of memory, Germany not only honors its forebears but equips its descendants with the tools to navigate tomorrow, ensuring that the cultural tapestry of the Black Forest and the nation it cradles remains vibrant and whole. In this hidden vault, the spirit of German culture finds its most secure home, a beacon of hope buried deep where the mountains themselves stand guard.

Image by joergens.mi.