A Love-Hate Affair With Words

Mark Twain had a knack for turning irritation into laughter. Few writers could complain as brilliantly as he did, and nowhere is this talent more obvious than in his famous essay “The Awful German Language.” At first glance, the title seems like a blunt dismissal, a declaration that German is unwieldy, unforgiving, and perhaps not worth the trouble. Yet the more one reads, the clearer it becomes: Twain’s tirade is not only a list of grievances but also a declaration of fascination. His exaggerated frustration hints at a deeper affection for the very language he seemed to mock.

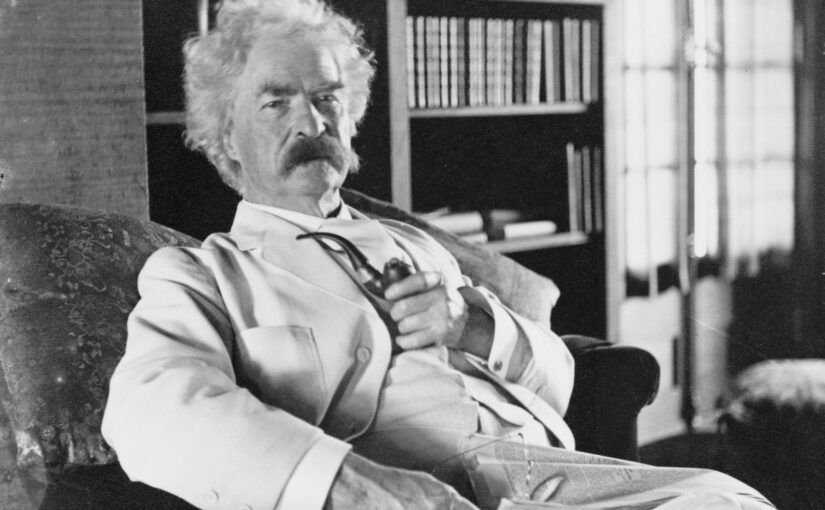

Twain in Germany

To understand why Twain wrote the piece, one has to consider the context of his travels. During the late 1870s Twain journeyed through Europe with his family, spending extended time in Heidelberg. Germany was fashionable among well-to-do Americans who wanted both culture and affordable education. Twain enrolled his eldest daughter in school, immersed himself in the intellectual atmosphere, and began wrestling with the language that surrounded him.

He attended lectures, conversed with locals, and attempted serious study of German grammar. The effort often left him exasperated, but it is telling that he did not give up. He kept notebooks, tried his hand at translation, and shared comical observations about his progress. Unlike a tourist who shrugs at a menu he cannot read, Twain cared too much to ignore the difficulty. His irritation testified to his persistence.

The Awful German Language and Its Place in Twain’s Work

“The Awful German Language” first appeared as an appendix to A Tramp Abroad in 1880. The book chronicled Twain’s European travels with his characteristic blend of observation and satire. The essay stands out because it abandoned narrative for an open complaint about grammar, vocabulary, and syntax. It reads less like a travelogue and more like a stand-up routine, with Twain performing the role of a bewildered foreigner beaten down by grammar tables.

That Twain included the essay in a book intended for broad audiences shows he believed readers would not only commiserate but also laugh alongside him. In fact, his portrait of German as both majestic and absurd became one of the most widely remembered parts of the entire volume.

The Linguistic Quirks That Drove Him Mad

What precisely bothered Twain so much? For starters, the monstrous compound words that appear in German. To him, seeing a twenty-letter construction felt like stumbling upon a beast with too many heads. The rules allow endless stringing together of smaller words, so that concepts thought trivial in English suddenly resemble small novels when expressed in German. Modern students still chuckle with recognition when presented with intimidating examples like “Krankenwagenfahrerlaubnisprüfung,” a term that seems to have no right existing outside a spelling competition.

Another torment was gender. In English, a table is an object. In German, a table is masculine. A fork is feminine. A little girl, oddly, is neuter. Twain threw up his hands at such arbitrary decisions and poked fun at the idea that inanimate objects needed these grammatical costumes in the first place.

Cases added another layer of agony. In German, the role a word plays in a sentence changes its ending, so learners must juggle nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive. Twain joked about how a single sentence might twist and tumble under these rules until the original thought disappeared behind a wall of suffixes.

And then, there is the word order. German has the habit of kicking its verbs to the end of sentences, especially in subordinate clauses. The result is that a listener can sit through half a paragraph before discovering what the speaker meant to do. Twain captured the feeling of faithfully waiting at the train station of a sentence, only to have the crucial verb arrive long after schedule.

Satire or Ridicule?

At first glance, Twain’s essay sounds like mockery. Yet anyone familiar with his style knows he rarely dished out pure cruelty. His satire rested on exaggeration, on stretching frustration until it snapped into comedy. He delighted in absurdity, not in meanness. By chronicling his struggles with German in such dramatic fashion, he was not only venting but also celebrating the richness of the language.

In reality, ridicule and admiration often travel together in Twain’s work. He teased Americans just as sharply as Europeans, and he tended to poke fun at what he admired enough to observe closely. His supposed hatred of German was therefore more a theatrical performance than a genuine dismissal.

Loved by Readers Who Speak German

The irony is that German speakers themselves adored his essay. Instead of taking offense, many recognized their language in his caricature and laughed in agreement. Students of German, whether in the nineteenth century or today, feel an instant bond with Twain when reading his descriptions. His words capture the timeless frustration of wrestling with declensions and dictionaries.

This broad appeal has given the essay a surprisingly long life. Linguists cite it as an example of outsider perspective, while teachers assign it to reassure beginners who feel overwhelmed. Twain, by airing his own comic failures, let others see that even a master of English prose could feel humbled by grammar exercises.

Twain’s Struggles and Modern Learners

Reading “The Awful German Language” today feels oddly familiar. Anyone who has tried to hold a conversation in German without tripping over cases knows the despair he described. The seemingly endless compounds still appear in newspapers, and the gender system has not grown any friendlier. Digital apps and textbooks may have sped up learning, but the core difficulties remain.

Yet just like Twain, many students discover that their annoyance comes paired with affection. The very quirks that seem impossible at first become sources of pride once mastered. The compounds that cause terror eventually deliver precision, the cases enrich expression, and the verb-at-the-end rule grants suspense. Twain’s rant captures the earliest stage of this journey, where humor becomes a survival strategy.

Awful and Wonderful at the Same Time

So did Twain truly hate German? The evidence suggests otherwise. His obsession, his patience, and the sheer energy he poured into his comedic complaint reveal something deeper than rejection. It is hard to imagine him devoting so many pages, jokes, and exasperated metaphors to a language he felt only contempt for.

Instead, Twain seems to reveal a paradox that many learners know well: the language that drives you to despair can also capture your affection. The awful is inseparable from the wonderful. Every syllable that made him groan also kept him coming back, notebook in hand, ready to duel once again with declensions and spellings.

From “Awful” to Unforgettable

“The Awful German Language” is more than a grumble about grammar. It is the record of a great humorist grappling with linguistic challenge and transforming defeat into art. Twain’s struggle mirrors our own when we attempt foreign languages, full of frustration yet tinged with delight. Ultimately, his essay reminds us that mockery can be a form of love, and that sometimes the deepest admiration hides inside the loudest complaint. Twain may have called German awful, but by writing about it so memorably, he proved it was also unforgettable.