The Mediterranean world of the fifth century witnessed many unexpected transformations, but few were as striking as the sight of a Germanic kingdom thriving on the sun-baked shores of North Africa. For nearly a century, the Vandals ruled from Carthage, that ancient Phoenician jewel turned Roman metropolis, creating a maritime empire that stretched across the western Mediterranean. Their presence in a land so far from their northern European origins might seem almost improbable, yet the Vandal Kingdom represents a fascinating case study in cultural transformation, religious conflict, and the fluid nature of identity in late antiquity.

From Hispania to Carthage: The Rise of Geiseric’s Kingdom

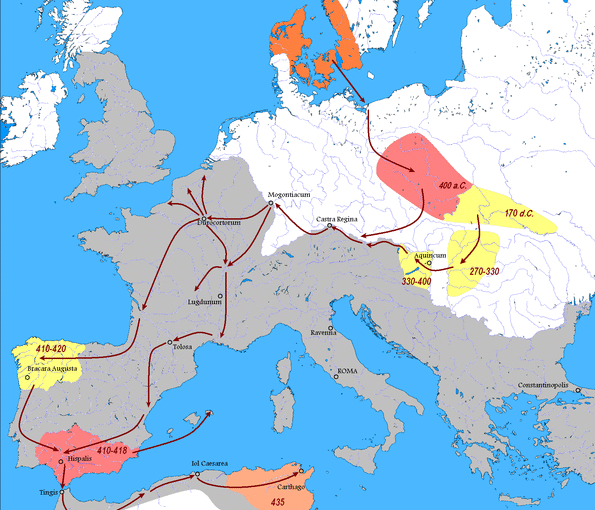

In 429 AD, approximately 80,000 Vandals crossed the narrow strait from Hispania into North Africa, embarking on a journey that would reshape the region’s political landscape. Led by the ambitious and strategically brilliant Geiseric (also spelled Gaiseric), these migrants were not simply raiders but a people seeking new lands to settle. They advanced steadily eastward through the coastal provinces, conquering territories in what is now Algeria and Tunisia.

The Western Roman Empire, already stretched thin by multiple threats, initially attempted to contain the Vandals through diplomacy. In 435, a treaty granted them control of Numidia and Mauretania as federated allies. But Geiseric had grander ambitions. On October 19, 439, in a surprise move that caught the city unprepared, Vandal forces entered Carthage while most inhabitants were attending races at the hippodrome. The fall of Carthage was more than a military victory. It was a symbolic earthquake that reverberated throughout the Roman world.

From Carthage, now his capital, Geiseric styled himself King of the Vandals and Alans, acknowledging his Alan allies in the royal title. His fleet soon dominated the western Mediterranean, and by the mid-440s, the Vandals had seized Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta, and the Balearic Islands. This maritime empire controlled vital grain shipments and trade routes, effectively strangling the Western Roman Empire’s economic lifeline. The Vandal sack of Rome in 455, though less destructive than legend suggests, demonstrated their reach and power.

Political Legacy and Byzantine Reconquest

The Vandal Kingdom endured for 99 years, outlasting many of its contemporary Germanic successor states. Geiseric’s death in 477 brought a period of normalized relations with the Eastern Roman Empire, though religious tensions simmered beneath diplomatic niceties. The kingdom maintained its independence and maritime dominance through efficient administration and control of North Africa’s agricultural wealth. However, the Vandals’ grip on the region ultimately proved vulnerable to Byzantine ambitions.

In 533, Emperor Justinian dispatched his brilliant general Belisarius to reclaim North Africa. The campaign was swift and decisive. At the Battle of Tricamarum in December 533, the Vandal forces fought valiantly but broke when their commander Tzazo fell in battle. King Gelimer, the last Vandal monarch, surrendered in 534 after a siege at Mount Pappua, bringing the kingdom to an end. North Africa was reintegrated into the Byzantine Empire, and the Vandals themselves were either assimilated into the local population or dispersed throughout Byzantine territories.

The Religious Divide: Arian Christianity and Catholic Persecution

Religion defined much of the Vandal experience in North Africa and shaped how contemporary writers remembered them. The Vandals adhered to Arian Christianity, a theological position that viewed Christ as subordinate to God the Father rather than co-equal in the Trinity. This put them at odds with the predominantly Nicene (Catholic) Christian population they now ruled.

From the beginning of their invasion in 429, Vandal kings pursued policies that ranged from discrimination to outright persecution of Catholic Christians. Geiseric seized basilicas, expelled intransigent bishops from their cities, and worked systematically to advance the Arian church while suppressing Nicene practices. The intensity of these religious conflicts sets Vandal Africa apart from other Germanic kingdoms of the period, where religious coexistence was often more peaceable.

Hunaric, Geiseric’s son, intensified these policies during his reign from 477 to 484. Catholic bishops faced exile to remote desert regions, churches were confiscated and handed to Arian clergy, and some priests who resisted were tortured or executed. Eugenius, bishop of Carthage, suffered public humiliation and exile for refusing to embrace Arianism. The persecution was documented in vivid detail by contemporary writers like Victor of Vita, whose accounts profoundly influenced how later generations viewed the Vandal period.

Yet modern scholars suggest these religious policies served political as well as theological purposes. The Vandals may have seen the Catholic hierarchy as a potential fifth column loyal to Constantinople, and Arianism became a means for Vandal kings to maintain unity among their followers and distinguish themselves from the Roman African majority.

Society and Culture: Blending and Transformation

Despite religious tensions, Vandal and Roman African societies were far more intertwined than traditional narratives of barbarian invasion might suggest. Archaeological and literary evidence reveals substantial social mixing, with Vandal and Roman African elites living in the same urban environments and adopting each other’s customs, dress, and lifestyle.

Recent scholarship emphasizes transformation rather than destruction. The Vandals did not obliterate Roman African culture but rather created a hybrid society where late antique educational traditions and literary culture continued to flourish. Authors and scholars worked under Vandal patronage, and the region maintained its intellectual vitality. Some historians, like Averil Cameron, have even suggested that Vandal rule may not have been entirely unwelcome to North Africa’s population, as the previous Roman landowners were often unpopular.

Archaeological investigations in Carthage reveal a complex picture. Excavations show evidence of both neglect, such as deteriorating sections of the city wall and infrastructure gaps, and new construction projects and adaptive reuse of buildings during the fifth and sixth centuries. The city remained a vibrant urban center, though its character evolved under Vandal administration. The archaeological record at Carthage preserves layers from multiple periods, including Vandal and early Christian phases embedded within the broader Punic, Roman, and later Arab stratigraphic sequence.

Coinage and Administration: Signs of Sovereignty

One of the clearest material traces of Vandal sovereignty is their distinctive coinage. After capturing Carthage in 439, the Vandals established their own minting operation, producing coins that bore witness to their economic and political control. Recent numismatic research has focused intensively on analyzing the systematic production, denominations, and iconography of these Vandal issues, using them as keys to understanding the kingdom’s economic history and administrative structures.

Vandal coins have been found far beyond North Africa, evidence of the kingdom’s extensive trade networks. Excavations at sites in Egypt, for instance, have revealed that Vandal coins minted in Carthage circulated widely throughout the eastern Mediterranean, particularly the small denomination bronze pieces known as nummi minimi. After Justinian’s reconquest, Byzantine coins minted in Carthage continued to flow through these same networks, demonstrating the continuity of commercial systems.

The Vandals adapted Roman administrative structures to their needs, establishing a government capable of extracting taxes and maintaining control over grain production and maritime trade routes. Their command of Africa’s agricultural resources and shipping lanes dealt a significant blow to the Western Roman Empire’s fiscal stability, contributing to its eventual collapse.

Legacy: Bridge Between Two Worlds

Modern historians increasingly view the Vandal Kingdom not as an interruption of North African history but as a bridge between the late Roman and Byzantine periods. Institutional continuities and the preservation of urban structures facilitated the region’s relatively smooth reintegration into the Byzantine Empire after 534. The Vandals left behind a political legacy, distinctive religious history, and material evidence in the form of coins and archaeological layers, but their language and ethnicity rapidly disappeared from the historical record.

Distinctly “Vandal” cultural markers in material culture are remarkably rare. Most artifacts remain Roman African in character or show hybrid influences rather than purely Germanic forms. This scarcity reflects the speed with which the Vandal minority was absorbed into the majority culture that surrounded them. The Vandal name itself, which would later become synonymous with wanton destruction in European languages, tells us more about later medieval and Renaissance perceptions than about the actual practices of Geiseric’s kingdom.

Today, the Vandal period endures primarily through numismatic collections, church records documenting religious controversies, legal documents, and the stratified archaeological remains of cities like Carthage. These traces reveal a kingdom that was neither a simple destroyer of Roman civilization nor a foreign implant that left no mark. Instead, the Vandals represent one chapter in North Africa’s long history of cultural synthesis, a century when Germanic warriors became Mediterranean naval powers, and when the shores of Africa hosted a kingdom unlike any that had come before.

Image: Vandal migration from northern Europe to north Africa.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.