Around the year 98 CE, the Roman senator and historian Tacitus composed a short ethnographic work called Germania. In it, he described the peoples living beyond the Rhine and Danube with curious fascination and thinly veiled moral purpose. Their diet, he wrote, was refreshingly primitive: wild fruits, fresh game, and curdled milk. No sauces, no flourishes, no ceremony. Just hunger expelled in the simplest way possible.

To Tacitus, this austerity was deliberate. The ancient Germans weren’t just eating simply because they lacked Roman sophistication. They embodied something Rome had lost: restraint, toughness, a kind of muscular virtue rooted in the cold northern soil. But his Germania was less a travel diary and more a morality tale written for his fellow Romans, whom he saw as bloated with excess and decadence. The barbarians beyond the frontier, with their plain porridge and coarse bread, were meant to serve as a mirror.

So what did simplicity actually mean in a world before abundance? And what did Romans really see when they looked across the table at their northern neighbors?

The Savage Banquet: Roman Fantasies of the North

Roman and Greek writers loved to dramatize the eating habits of the peoples they considered uncivilized. The Greek polymath Poseidonius, writing in the first century BCE, depicted Germanic feasts as barbaric spectacles where warriors devoured limb-sized chunks of roasted meat, washing them down with undiluted wine and milk. It was a scene straight out of collective nightmare, designed to titillate and horrify readers in equal measure.

Even more bizarre was the account by the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, who claimed to have recorded the first authentic Germanic recipe: raw meat beaten soft inside a leather hide, then warmed between hot stones. A kind of proto-tartare for proto-barbarians.

These stories reveal far more about Roman anxieties than about actual northern foodways. Rome defined itself through refinement and order. Its cuisine celebrated complexity, its banquets were theater, its feasts were statements of civic identity. To imagine the Germans feasting with abandon on bloody meat, guzzling fermented grain, and belching garlic and onions at dawn (as the Roman writer Sidonius Apollinaris later complained) was to define what Rome was not.

But imagine, just for a moment, the reality behind the stereotype. Smoke curling through the smoke-hole of a longhouse. The clang of iron kettles hanging over open flames. The scent of barley porridge thickening in animal fat, mingling with the earthy aroma of root vegetables pulled from storage pits still cold with winter frost. This was no feast of savagery. It was survival, careful and communal.

What Archaeology Says: The Grain, the Root, the Rare Roast

Excavations of Germanic settlements tell a different story than the lurid accounts of Roman writers. Archaeological evidence shows that most ancient Germans were subsistence farmers, not nomadic hunters. They grew barley, spelt, oats, and legumes like beans, lentils, and peas. They kept small herds of cattle, sheep, and horses, but these animals were far tinier than modern breeds and provided limited meat.

The staple meal was porridge. Coarsely ground grains soaked overnight, then boiled in water or milk and enriched with whatever fat was available. Pork drippings if a pig had been slaughtered, beef tallow if not. Sometimes the porridge was flavored with wild herbs, hazelnuts, or honey when the harvest allowed. Women baked flatbreads in the ashes of the fire, unleavened loaves that hardened quickly and had to be eaten fast or softened in broth.

Meat was rare. Wild game accounted for less than one percent of the bone remains found at most settlements, though in some regions it reached up to thirty percent. Forests could not sustain large enough populations of deer, boar, and aurochs to feed settled communities, especially when competing with wolves, bears, and lynxes. Hunting was supplementary, not foundational.

Salt was so precious that wars were fought over brine springs. Without it, preservation was nearly impossible. So when a pig was slaughtered or a deer brought down, the community cooked as much as possible in communal iron kettles and ate until nothing remained. These feasts weren’t gluttony. They were necessity dressed up as celebration, a way to honor abundance in a landscape defined by scarcity.

Kettles and Kinship: Food as Social Glue

The communal kettle wasn’t just a cooking vessel. It was the most valuable possession a clan could own, a symbol of solidarity and shared fate. To gather around the kettle meant you belonged. To be excluded was social death.

Contrast this with Roman dining culture. In Rome, meals reinforced hierarchy. The quality of your couch, the dishes you were served, the wine you drank, all signaled your rank. Dining was performance, a way to display wealth, taste, and civic virtue. The discus, a small individual plate from which the German word Tisch (table) derives, symbolized personal consumption within a collective framework.

For the Germans, food was less about display and more about survival and cohesion. A shared meal after the harvest, a feast following a successful hunt, these moments bound families and tribes together in ways Rome’s elaborate banquets, for all their sophistication, could not replicate. Restraint, mutual dependence, and the harsh pragmatism of a cold climate shaped not just what they ate, but how and why.

Linguistic Conquest: The Words Rome Left Behind

When Roman legions finally withdrew from the Rhine frontier, they left behind more than crumbling forts and abandoned roads. They left a culinary vocabulary that would outlast the empire itself.

The German words for cooking (Kochen), kitchen (Küche), cellar (Keller), bowl (Schüssel), cup (Becher), and mortar (Mörser) all derive from Latin. So do the names for most herbs and spices: pepper, cinnamon, mint, fennel. Even vegetables like cabbage and fruits like cherries carry Roman echoes in their German names.

This was colonization of a different kind. Rome’s legions may have failed to subdue the Germanic tribes militarily, but Roman agriculture, Roman cuisine, and Roman language seeped into the north anyway. The very tools and techniques used to prepare food became linguistic monuments to an empire that no longer existed.

It’s a reminder that cultural conquest often happens not through force, but through the stomach. The Romans who marinated beef in vinegar to preserve it on Alpine campaigns may have inadvertently invented the predecessor to Rheinischer Sauerbraten, though the connection remains unproven. What is certain is that the linguistic and culinary legacy of Rome endured long after its political power collapsed.

The Cycle of Virtue and Decadence

Tacitus worried that Roman decadence would invite disaster. He was right, though not for the reasons he imagined. By the time Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine in waves during the fourth and fifth centuries, Rome was a shadow of its former self. The Western Empire fell not because it lacked military might, but because it had lost cohesion, purpose, and the will to defend its sprawling borders.

Centuries later, the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun would articulate a theory that seemed to fit Tacitus’s fears like a glove. Prosperity breeds softness, Khaldun argued. Civilized urbanites forget the values that made them strong. Their wealth attracts hungry outsiders who retain the discipline and hunger the rich have lost. Eventually the outsiders conquer the decadent elites, grow prosperous themselves, and the cycle begins anew.

Was Germanic dietary simplicity ever really linked to moral simplicity? Probably not in any meaningful way. But the idea persisted because it’s seductive. We want to believe that restraint equals virtue, that hunger sharpens character, that abundance corrupts. The truth is messier. The Germans ate simply because their environment demanded it. The Romans ate elaborately because theirs allowed it. Neither was inherently more virtuous.

Yet the cycle Khaldun described, the eternal oscillation between austerity and excess, discipline and decadence, continues to haunt civilizations. Perhaps because it contains a kernel of uncomfortable truth.

The Fire and the Kettle

Picture a cold night somewhere beyond the Rhine. The wind cuts through the forest, rattling bare branches. Inside a longhouse, smoke spirals upward through the thatch. A kettle hangs over the fire, its contents bubbling softly. Barley porridge thickens, enriched with just enough fat to make it filling. A woman pulls flatbread from the embers, its crust blackened and fragrant. Children huddle close, waiting.

This is the meal Tacitus described with such simplicity. But simplicity isn’t the same as insignificance. In that kettle, in that shared bread, lay the bonds that held communities together through long winters and uncertain harvests. In the absence of Roman refinement, the ancient Germans built something else: resilience.

Perhaps civilization’s flavor has always depended on the tension between hunger and satisfaction. Too much comfort and societies grow brittle. Too much scarcity and they cannot flourish. The ancient Germans understood this balance instinctively. They ate simply not because they lacked imagination, but because survival required it. And in that simplicity, they found something Rome, for all its grandeur, had begun to lose: a shared table, a common cause, and the knowledge that tomorrow’s meal was never guaranteed.

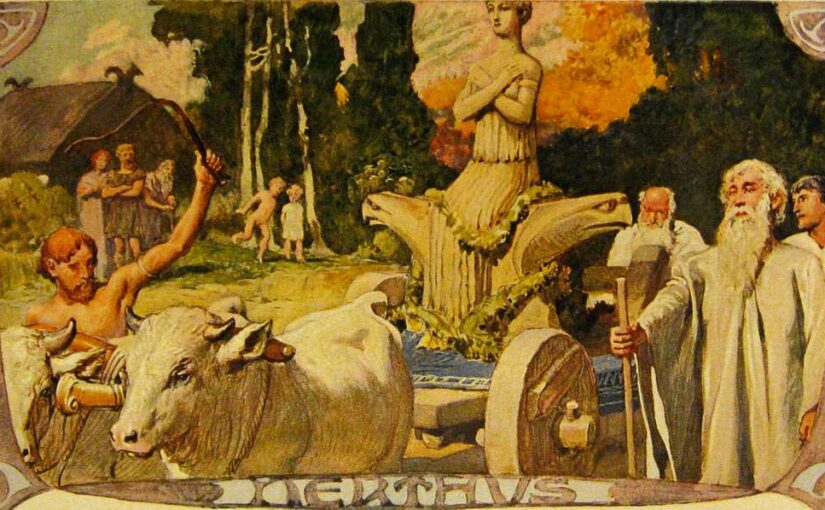

Image: Spectators watch as the processional wagon of the Germanic goddess Nerthus moves along, inspired by Tacitus’ description of the Germanic custom in his first century AD work Germania. Doepler, Emil. ca. 1905.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.