The story of German as a foreign language in Europe unfolds like a tapestry woven from threads of trade, faith, and power. From the misty beginnings of the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment’s close around 1800, learning German meant bridging worlds: the rugged heartlands of the Holy Roman Empire with the bustling ports of the Baltic and the scholarly halls of Italy. This sketch traces that journey, focusing on the teaching and learning of German beyond its native speakers. It is not an exhaustive chronicle but a glimpse into how a Germanic tongue evolved from a tool of survival to a key for cultural prestige.

This history matters because it illuminates Europe’s linguistic mosaic. In an era when Latin dominated as the lingua franca of the elite, German’s rise as a foreign language reflected shifting dynamics. Merchants needed it for commerce; diplomats for alliances; scholars for texts on theology and science. The “history of German language learning” reveals not just pedagogical methods but the continent’s interconnectedness. As borders blurred through migration and conquest, German became a vessel for ideas, influencing everything from Baltic folklore to British philosophy. By examining who learned it, how, and where, we see how “German as a foreign language” shaped “European linguistic history” long before modern nation-states. This exploration draws on early texts and trade records, offering a window into a quieter chapter of “medieval language education.”

Early Beginnings (Old High German Sources)

The roots of German as a foreign language dig deep into the ninth century, marking the dawn of the Old High German period. This era, roughly 750 to 1050, saw the language standardize amid Christianization and Carolingian reforms. The earliest evidence comes not from grand treatises but humble glosses, word lists crafted by outsiders navigating Germanic lands.

Consider the Kassel glosses, a modest Romance-Old High German vocabulary compiled around 820 by a West Frankish traveler. Found in the Hessian town of Kassel, this list paired Latin and Romance terms with their German equivalents, like domus for house or aqua

for water, aimed at basic communication in Bavaria. The traveler, likely a pilgrim or envoy from the Frankish west, sought to make himself understood amid the Bavarian dialect’s guttural tones. Such glosses were practical lifelines, born of necessity rather than scholarship.

Another gem is the Pariser Gespräche, or Paris Conversations, dating to the late eighth or early ninth century. Preserved in a Paris manuscript, this bilingual dialogue offers phrases for everyday exchanges: greetings, bargaining, and directions. It imagines a Romance speaker haggling in a German market or seeking shelter in a monastery. These texts hint at the motivations driving early learners. Trade pulled merchants across the Alps and Rhine, where German dialects facilitated deals in furs and amber. Religion spurred monks and missionaries; the spread of Christianity under figures like Boniface demanded vernacular aids to convert and communicate. Diplomacy, too, played a role, as Frankish courts intertwined with emerging German principalities.

In these beginnings, learning was informal and immersive. No classrooms existed; instead, travelers memorized phrases through repetition, perhaps aided by bilingual informants in hostels or markets. This oral tradition laid the groundwork for German’s foreign allure, proving that even in the Dark Ages, language was a bridge over cultural chasms. As the millennium turned, these sparks would ignite wider flames of exchange.

Medieval Learning and Cultural Exchange

By the High Middle Ages, from 1000 to 1500, German’s spread as a foreign language quickened, fueled by economic booms and ecclesiastical networks. Neighboring regions felt its pull first: France to the west, with shared borders sparking cross-Rhine interactions; Italy to the south, where Lombard merchants eyed Alpine passes; the Low Countries, with their Flemish-German trade hubs; and Scandinavia plus the Baltic, where Viking descendants turned to commerce.

The Hanseatic League, that powerhouse of northern trade from the 12th century, was a prime catalyst. This confederation of cities from Lübeck to Novgorod knit Europe in a web of wool, herring, and timber. German became the league’s working language, drawing Baltic locals like Estonians and Latvians into its orbit. In Riga or Tallinn, apprentices learned German phrases for contracts and ledgers, blending dialects into a pidgin for ports. Monastery schools amplified this; Benedictine and Cistercian houses, dotting the landscape from Flanders to Pomerania, taught German to clerics managing estates. Figures like the 13th-century monk Berthold of Regensburg preached in German, inspiring foreign novices to study his sermons for doctrinal depth.

Who pursued this learning? Merchants topped the list, pragmatic souls like the Italian banker Francesco Datini, whose 14th-century diaries note German vocabulary for wool prices. Clerics followed, translating Bibles or hagiographies; envoys from Polish courts mastered it for imperial negotiations. Nobles, too, dipped in, especially in borderlands where marriages sealed alliances.

Methods were rudimentary yet effective. Oral practice dominated: shadowing native speakers in markets or taverns built fluency. Glossaries evolved into fuller lexicons, like the 12th-century Vocabularius Rimberti, a Latin-German guide for missionaries in the east. Translation exercises, often in scriptoria, paired psalms or chronicles. No standardized curricula existed, but immersion in multilingual environments honed skills. In the Baltic, for instance, Swedish traders picked up Low German via songs and sagas shared around fires.

This era’s “medieval language education” was less about grammar than utility, embedding German in Europe’s cultural exchange. As crusades and fairs proliferated, the language wove into the continent’s fabric, setting the stage for print’s revolution.

Early Modern Developments (1500–1800)

The Renaissance and Reformation transformed German from a regional tool to a language of ambition. From 1500 to 1800, motivations shifted: diplomacy grew with Habsburg sprawl; scientific exchange boomed via printing presses; travel surged with Grand Tours; and cultural prestige attached to German thinkers like Luther.

Printing, invented by Gutenberg around 1450, was the game-changer. By 1500, German texts flooded Europe: Luther’s 1522 New Testament translation, rendered in accessible High German, drew foreign scholars to Augsburg and Wittenberg. Grammar books proliferated; Johann Fischart’s 1570s adaptations of Rabelais included bilingual glosses, easing French readers into German satire. Didactic materials like conversation manuals emerged, such as the 1596 Colloquia familiaria by Christopher Ligurinus, offering dialogues for travelers.

German’s status rose, yet it trailed Latin’s universality, French’s courtly elegance, and Italian’s artistic flair. Still, in Protestant circles, it rivaled Latin for theology; Leibniz’s 17th-century philosophy texts lured Dutch and English intellectuals. In diplomacy, the 1648 Peace of Westphalia demanded German proficiency for envoys navigating the Empire’s patchwork states.

Learners diversified: diplomats like England’s Sir Thomas Roe studied it for 1610s missions; scientists, including Sweden’s Olof Rudbeck, pored over German herbals. Methods formalized; Jesuit colleges in Prague taught via grammar drills and declensions. Phrasebooks, like the 1680 German and English Dictionary by William Alms, targeted English merchants with themed vocabularies: shipping, customs, hospitality.

This period’s “history of German language learning” highlights adaptation. Academies in Leiden or Bologna hosted German lectures, blending oral drills with written exercises. By 1800, German edged toward modernity, its foreign study a marker of Enlightenment curiosity. Yet, as French ascended post-Revolution, German retained a niche in trade and intellect.

Three Regional Case Studies

The Baltic Region: Hanseatic Trade Dialects and Their Educational Impact

In the Baltic, German’s story is one of maritime might. The Hanseatic League’s 13th to 17th-century dominance turned cities like Visby and Danzig into polyglot hubs. Low German dialects became trade’s tongue, with locals learning via apprenticeships. A 14th-century guild record from Reval (Tallinn) details Swedish youths memorizing cargo terms: Schiff for ship, Ladung

for load. Educational impact lingered; by 1600, Latin schools in Riga incorporated German readers, fostering a bilingual elite that shaped Estonian literature. This case underscores trade’s role in “German as a foreign language,” blending dialects into enduring cultural hybrids.

The British Isles: Examples of Early German Language Study and Cultural Interest in German Thought

Across the Channel, Britain’s encounter with German brewed from the 16th century, sparked by Protestant ties and Hanoverian links. Queen Elizabeth I’s court hosted German envoys, prompting noble tutors like Roger Ascham to include German in curricula. By 1700, Oxford don William Boswell compiled a German grammar, drawing on Luther’s texts for divinity students. Cultural interest peaked with fascination for Pietism; John Wesley’s 1730s journals note studying German hymns for Methodist revivals. This study, often private and text-based, wove German thought into English Romanticism, illustrating how “European linguistic history” crossed seas through faith and philosophy.

The Mediterranean (Italy/Spain): Evidence of Bilingual Phrasebooks, Merchant Vocabularies, and Scholarly Exchanges

Southern Europe embraced German later, from the 15th century, via Alpine trade and Renaissance humanism. In Italy, Venetian merchants used phrasebooks like the 1490 Vocabolista in lingua Tedesca et Italiana, listing terms for glass and silk deals: Spiegel for mirror, Stoffe for fabrics. Spanish evidence appears in 16th-century Seville logs, where conversos fleeing Habsburg lands learned German for imperial service. Scholarly exchanges shone in Bologna, where anatomist Andreas Vesalius studied German medical tracts in the 1540s. These bilingual tools, simple yet vital, highlight Mediterranean “medieval language education” as a bridge between commerce and intellect.

Modern Scholarship and Research Gaps

Contemporary historical linguistics has unearthed treasures illuminating this era. Scholars like Kurt Gustav Gaebel, in his 1970s analyses of glossaries, decoded the Kassel and Paris texts, revealing phonetic shifts. Philologists at the University of Munich, through projects like the Deutsches Wörterbuch, trace loanwords showing German’s influx. Digital archives, such as the Bavarian State Library’s manuscripts, aid in mapping spread patterns.

Yet gaps persist. Sources are scarce; many glosses perished in wars, leaving oral traditions undocumented. Methodological hurdles include dialect fragmentation, complicating reconstructions. Who were the unsung learners, like female traders or rural clerics? Future studies promise much: AI-driven text analysis could revive faded inks, while interdisciplinary work with archaeology might uncover trade-route phrasebooks. Promising directions include Baltic dig sites and Italian merchant archives, enriching our grasp of “history of German language learning.”

German as a foreign language before 1800 was more than a skill; it was a conduit for Europe’s soul. From ninth-century glosses to Enlightenment grammars, it facilitated trades that built empires and ideas that sparked reforms. This sketch shows its evolution: practical in medieval ports, prestigious in modern salons. By connecting regions from Baltic shores to Mediterranean villas, German fostered a shared linguistic heritage, underscoring how foreign tongues knit the continent. As we reflect on this “European linguistic history,” it reminds us that languages thrive not in isolation but in dialogue, much as they do today.

Recommended Sources for Further Reading

- The History of German as a Foreign Language in Europe

This scholarly article offers a comprehensive overview in English of German’s teaching and learning across Europe up to 1800, including early medieval examples.

URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/1759753614Z.00000000026 - The Study of Foreign Languages in the Middle Ages (JSTOR)

This classic paper examines foreign language education in medieval Europe, with references to Germanic languages and early teaching methods relevant to German’s role.

URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2847789

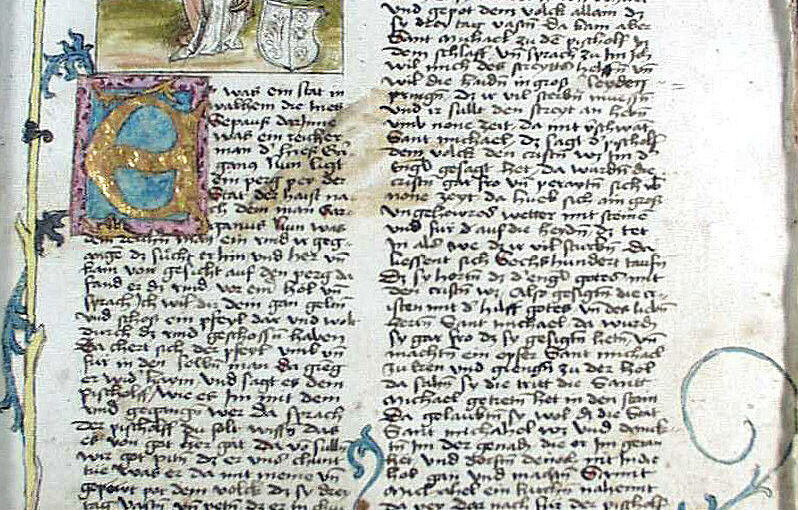

Image: Der Heiligen Leben Winterteil, ca. 1475 in Freising, Seite aus einer Handschrift aus dem Benediktinerstift Weihenstephan, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München – Signatur: Cgm 504.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.