German continues to assert its position as the most widely spoken language in Europe, with 94 percent of its global speakers residing on the continent. This enduring dominance persists despite the upheavals of two world wars and the rise of English as a lingua franca. The Fourth Report on the Status of the German Language, a comprehensive study by a team of 22 scientists from the Union of German Academies of Sciences and Humanities in collaboration with the Darmstadt Academy for Language and Literature, underscores this resilience. Presented at the Berlin Academy of Sciences in September 2025, the report examines German’s role across 15 European countries, highlighting both its institutional strength and the nuanced challenges it faces in multilingual settings.

German holds official status in seven European countries or regions, serving as more than just a communication tool in places like Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg. It also enjoys recognition in East Belgium and South Tyrol in Italy, where regional governance and education incorporate it fully. Beyond these core areas, German persists as a minority language in eight additional nations, including Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Poland, Czechia, France, and Denmark. This broad footprint, stretching from southern Denmark to the Volga River, marks German as historically unparalleled among European languages in geographic spread. The report’s country profiles reveal that while official recognition bolsters its vitality in the west, minority contexts often demand ongoing advocacy to prevent erosion.

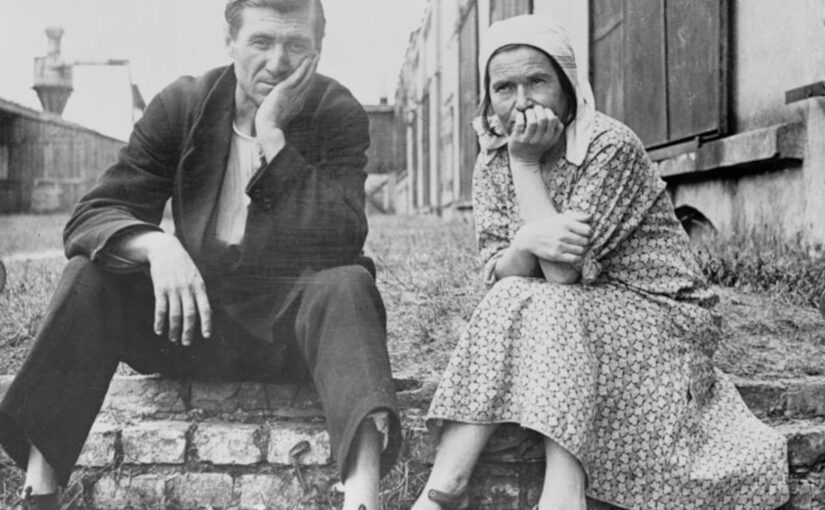

The expansive distribution of German stems not from colonial ventures like those of English, Spanish, or French, but from centuries of migration driven by invitation and opportunity. As early as the Middle Ages, German settlers moved eastward at the behest of local princes, establishing communities that embedded the language deep into diverse landscapes. This organic expansion created a mosaic of dialects and standard forms without the imperial overlay seen elsewhere. Even after significant territorial losses following the world wars, which contracted the German-speaking area, the language has maintained remarkable stability. Today, approximately 95 million people speak German as their first language, with another 30 million using it as a second, positioning it as Europe’s second most spoken tongue after Russian and boasting the third-highest number of online entries globally, behind only English and Spanish.

Regional dynamics paint a varied picture of German’s health. In Hungary and Romania, encouraging trends emerge, with more individuals identifying as German-speaking minorities and enrolling in language programs. Bilingual schools have proliferated, and improved minority rights have diminished the stigma once attached to German heritage, fostering a revival that contrasts with past hostilities. Similarly, in Czechia, the language’s status as a minority tongue was elevated in 2024, leading to enhanced promotion in education and cultural initiatives, particularly in the western regions where historical ties run deeper. These developments signal that proactive policies can reinvigorate linguistic communities, turning potential decline into sustainable growth.

Yet challenges abound in other areas, especially the so-called language islands of Poland, Russia, Czechia, and Ukraine, where isolated German-speaking pockets face gradual attrition. Here, speakers increasingly prioritize economic languages over heritage ones, and family transmission wanes as standardized variants taught in schools displace ancestral dialects. The report notes a broader erosion of dialects across Europe, as global learners and even minority members adopt a uniform High German, or Hochdeutsch, sidelining the rich, centuries-old regional forms that once defined local identities. This shift underscores a tension between preservation and adaptation, where the path to decline opens when communities no longer deem the language essential.

Multilingual nations like Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg illustrate the complexities of perception and policy. In Switzerland and Liechtenstein, High German often feels like an outsider, even carrying negative connotations despite its role in national media and administration. Local variants, enriched with unique vocabulary, compete with this perceived foreign standard, complicating language teaching in diverse settings. Luxembourg presents a stark post-World War II case, where German faced heavy stigmatization due to historical associations, yielding ground to Luxembourgish, a Moselle Franconian dialect, and French. As linguist Alexandra N. Lenz from the University of Vienna observes, language extends beyond functionality; societal attitudes, often untethered from linguistic science, profoundly shape its trajectory. Bilingual education and cultural policies thus play pivotal roles, either reinforcing German’s integrative power in core countries like Germany and Austria or exposing vulnerabilities in peripheral zones.

Institutions such as the Goethe-Institut and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) remain vital in countering these pressures. The Goethe-Institut’s global network promotes German through cultural programs and language courses, while DAAD scholarships draw international scholars, embedding the language in academic exchanges. However, the report warns of threats like institute closures and insufficient funding for foreign cultural initiatives, which co-finance overseas teaching. Experts like Christa Dürscheid from the University of Zurich and Ludwig M. Eichinger from Mannheim urge stronger support to sustain German’s reach, emphasizing that without such efforts, opportunities for learning and engagement could diminish. These bodies not only teach the language but also nurture the attitudes that ensure its cultural relevance amid Europe’s evolving diversity.

Looking ahead, German’s future in Europe hinges on navigating globalization’s currents, where English’s ubiquity tempts a monolingual drift, yet multilingualism persists as a continental strength. The report balances optimism with caution, celebrating German’s institutional foothold while lamenting dialect losses that dilute regional heritages. Preserving these local voices alongside a cohesive standard demands vigilant policies, from minority protections to innovative education. Ultimately, German endures as a bridge across cultures and a marker of identity for millions, weaving Europe’s historical tapestry into its modern narrative with quiet tenacity. As migration and policy evolve, the language’s adaptability will determine whether it thrives as a unifying force or fades into niche relevance.

Official Publication Page (Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung): This provides a detailed overview, including the report’s structure with 15 country profiles and thematic analyses on multilingualism and vitality. URL: https://www.deutscheakademie.de/de/aktivitaeten/publikationen/ausser-der-reihe/deutsch-in-europa-vierter-bericht-zur-lage-der-deutschen-sprache

Summary Article (Deutschland.de): Offers a concise English-language overview of the report’s findings, including speaker statistics and migration’s role in German’s stability. URL: https://www.deutschland.de/en/news/german-continues-to-thrive

Image: West Prussia, Russian-German refugees Russia, a German farming couple from the Volga region in the Schneidemühl refugee camp (Posen-West Prussia border region). 1920-1925 ca. Deutsches Ausland-Institut (Bild 137).