Welcome to the Hall of Threadbare Geniuses

Germans have a particular fondness for calling their homeland “das Land der Dichter und Denker,” a phrase that rolls off the tongue with just enough theatrical flair to impress both tourists and locals. “Land of Poets and Thinkers” graces everything from airport billboards to school book covers. Names like Goethe and Schiller are conjured with reverence, as if contemporary teenagers, between TikTok scrolls and existential sighs, are secretly scratching out the next Faust instead of WhatsApp memes.

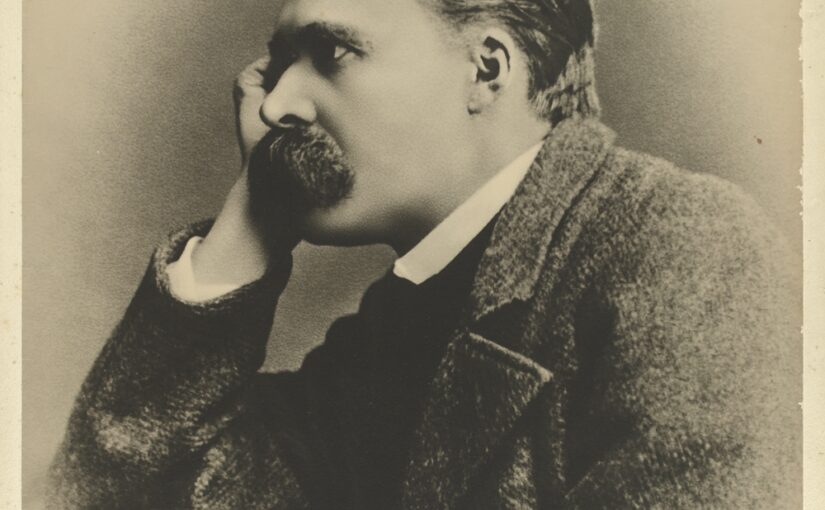

But here’s the twist. This grand tradition carries a sly, self-aware irony that only a nation with equal measures of self-confidence and self-doubt could uphold. Yes, Germany produced braniacs like Nietzsche, who was as famous for his philosophical provocations as for his flamboyant mustache. Yet, in this celebrated kingdom of genius, the most noteworthy minds frequently found themselves embroiled in controversy, tangled in debate, or packing up for a hasty departure.

The Paradox of Intellectual Grandeur

Amble through German history and one is struck by its dazzling paradoxes. This is the land where Luther stirred revolutions with a hammer and a thesis, Gutenberg sparked the print age, and Kafka made job anxiety seem almost comforting compared to waking up as a bug. German philosophy was brewed in university towns like Jena and Weimar, where city budgets sometimes favored poetry salons over palaces or paving roads. These were fertile grounds for grand ambition and even grander disappointment.

The pride in this tradition runs so deep it sometimes glosses over less convenient truths: the various moments when the poets and thinkers were politely, or, let’s face it, impolitely, shown the door. For every bronze statue of a ruminating philosopher in a town square, there lingers the memory of playwrights, scientists, and writers who found their ideas less cherished at home than they were abroad.

The Emigrating Genius: Deutschland’s Best Export

History loves a good homecoming, but European history loves an exile. Einstein, between revolutionizing physics and deploying his unruly hair for photographic effect, left Germany quickly as politics went from troubling to intolerable. Heinrich Heine, relentless with his satirical wit, fled to Paris, where his humor was sharper and his risk of censorship lower.

Despite the proud tradition of producing intellectual giants, Germany’s greatest export through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was arguably these very minds. A steady stream of philosophers, artists, and scientists left, often under less-than-amicable conditions, sparking the enduring question: How many Nobel Prizes might have remained if fewer geniuses had been forced to pack their bags?

Where Are the Thinkers Now? A Glance at the Modern German Classroom

Fast forward to the present. Germans are justly proud of their pantheon of thinkers, but today’s school experience reveals a comic gap between aspiration and reality. Ask a group of high schoolers if they’d rather explore metaphysics or pass the dreaded Abitur exam and see how quickly philosophical ambitions dissolve into practical survival tactics.

The education system, with its rigid curriculum and all-important standardized tests, has perfected the art of encouraging memorization over innovation. Students may know which year Kant published the Critique of Pure Reason, but how many dare to emulate his spirit of radical inquiry? Those with too much creative flair may find themselves asked to keep their originality at home for the afternoon, perhaps tucked discreetly next to their cell phones.

Meanwhile, the icons of German intellectual history remain ever-present but slightly intimidating, less like role models, more like distant relatives remembered at family dinners and approached with caution in essays and oral exams.

Goethe’s Ghost: Timeless, Proud, and Utterly Perplexed

No figure is more ubiquitous than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His silhouette adorns stamps, schools, and entire literary societies. Still, it’s easy to imagine Goethe’s ghost wandering the halls of a modern Gymnasium, peeking at multiple-choice questions on his own books with a bewilderment befitting a man who preferred wine and conversation to digital scantrons.

He, and the rest of the pantheon, would surely wonder at their fate: glorified in textbooks, referenced by politicians, yet greeted with sighs by teenagers cramming for tests. Perhaps, in some act of poetic justice, those who once championed Romantic inspiration are now invoked mostly as warnings against daydreaming in class.

Literary Legacy: A Feast of Creatives

The list of Germany’s luminaries remains dazzling: the Brothers Grimm and their deliciously twisted fairy tales, Schiller’s impassioned dramas, Kant’s categorical imperatives, and Thomas Mann’s marathon novels. Rilke, Hesse, Grass, the names resound in literary and philosophical canons worldwide.

It’s a tradition so rich that even schoolchildren, despite their complaints, are unlikely ever to escape it entirely. Anyone hoping for a world where German culture is only about sauerkraut and Christmas markets will be quickly disappointed by the avalanche of reading lists and earnest lecture tours.

The Last Laugh: Irony as an Enduring National Sport

There is something distinctly German about making a national slogan out of intellectual greatness, then using it to mask the awkward truths of persecution and neglect. Irony is woven into the very fabric of the phrase das Land der Dichter und Denker: a celebration that sometimes sounds like a gentle, knowing joke told at one’s own expense.

So where, everyone wonders, are the new poets and thinkers? Can brilliant minds flourish while tethered to standardized metrics? Or has the baton been passed to a world that demands efficiency and compliance over wild originality?

Germany’s proud legacy remains both badge and question mark, an open invitation for every new generation to reimagine what it means to think, to write, and, occasionally, to roll their eyes at whichever brainiac the teacher brings up next. The story is not finished, and as history shows, a truly committed poet or philosopher will find a stage, even if they have to invent it themselves.

So, raise a glass to the thinkers that were, the thinkers that left, and the ones quietly plotting their escape from the next exam. The land of poets and thinkers is still very much alive, even if its heroes sometimes disappear when the bell rings.

Image: Nietzsche by Gustav Adolf Schultze.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.