On February 8, 1950, the People’s Chamber of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) enacted one of the shortest laws in German legal history. Without prior discussion, the law was rubber-stamped within minutes. It consisted of just two succinct paragraphs:

Paragraph 1:

«The Head Office for the Protection of the National Economy, previously under the Ministry of the Interior, shall be transformed into an independent Ministry for State Security. The Law of 7 October 1949 on the Provisional Government of the German Democratic Republic (Law Gazette p. 2) is amended accordingly.»

Paragraph 2:

«This act shall come into effect on the date of its promulgation.»

Thus, the Stasi was created.

The Shield and Sword of the Party

The Ministry for State Security, better known as the Stasi, functioned as the secret police and intelligence service of East Germany for nearly four decades. Under the rule of the Socialist Unity Party (SED), the Stasi became the ultimate symbol of state repression. Its guiding principle was Lenin’s dictum that trust is good but control is better. In practice, this meant that surveillance, intimidation, and persecution became fundamental tools of governance.

For ordinary East Germans, the presence of the Stasi was not just a shadow hanging overhead. It was an everyday reality that seeped into every interaction, every conversation, and even private family life. The agency ensured loyalty to the regime not with persuasion but with fear. Like the Berlin Wall, which came to symbolize the division of the world during the Cold War, the Stasi represented the suffocating grip of authoritarianism on an entire society.

Erich Mielke: Ruthlessness Personified

One man became especially synonymous with the organization’s brutality: Erich Mielke. His career as a Communist enforcer stretched back to the early 1930s when he participated in the murder of two Berlin police officers. After fleeing Germany, he joined the Spanish Civil War, where he took part in Stalinist purges. By 1945, he returned to Berlin and quickly rose in the ranks of the East German security apparatus.

Mielke was not an intellectual, nor was he known for political acumen. What he lacked in subtlety he compensated for with loyalty to Stalinist ideology and brute force. He was vulgar, paranoid, and aggressive in his leadership style. Subordinates trembled under his tirades, which often included threats of death. His message was simple: enemies must be destroyed without hesitation. When he eventually became head of the Stasi, he applied this mindset to the entire population of East Germany.

Surveillance Without Limits

The Stasi was modeled after Soviet security organs such as the Cheka and KGB, and like them, it enjoyed almost unlimited power. Constitutional guarantees meant nothing. Letters were opened, packages rifled through, phone calls tapped, and private homes bugged. Infiltration of institutions was systematic: churches, political groups, universities, and workplaces all housed informants ready to denounce anyone suspected of disloyalty.

Mielke’s infamous instruction that “we must know everything” became the mantra of the agency. Suspicion was not based on specific actions but on the belief that every individual was a potential traitor. Even trivial behaviors could be recorded as “hostile-negative.” What mattered was not objective guilt but the perception of possible disloyalty to the socialist system.

Citizens found themselves living in a climate of deep mistrust. No one could be sure who was listening. Friends might be informants, family members could be coerced, and colleagues might file secret reports. This atmosphere of paranoia was by design. It prevented opposition from organizing effectively and undermined the basic trust needed for social life.

Destroying Lives through Psychological Warfare

Arrest and imprisonment were only part of the Stasi’s arsenal. Over the years, the agency refined a system of psychological repression intended to ruin lives without necessarily resorting to visible violence. Targets could lose careers, be forbidden to travel, or have their families torn apart. Smear campaigns spread rumors about adultery, alcoholism, or criminality.

These methods were devastatingly effective. Individuals under scrutiny often became isolated, losing friends, livelihoods, and even their sanity. Families broke apart under the strain. For those who attempted to escape the GDR, punishments included lengthy imprisonment, loss of parental rights, or in worse cases, lethal violence at the border.

Cross-Border Operations and Assassinations

The Stasi’s activities were not confined within East Germany. Its operatives carried out kidnappings and assassinations abroad. Dissidents and defectors were hunted down, sometimes with deadly consequences. Refugee helpers in the West became frequent targets. Some survived attempts on their lives, such as Wolfgang Welsch, who endured poisonings and shootings. Others, like Hans Lenzlinger or Michael Gartenschläger, paid with their lives.

These extraterritorial operations demonstrated the regime’s reach and ruthlessness. The Stasi was not merely an internal police force. It was a global intelligence agency working to eliminate threats wherever they appeared.

An Overbearing Apparatus

At its peak, the Stasi employed over 90,000 full-time staff spread across 26 departments, supported by an army of around 189,000 unofficial collaborators. This staggering network gave the GDR the highest ratio of secret police to citizens in modern history.

Informants were recruited through a mix of ideological conviction, blackmail, and intimidation. Doctors, psychologists, and teachers were assessed for vulnerabilities, and even serious crimes could be overlooked if the perpetrators agreed to collaborate. Rewards ranged from small luxuries such as cigarettes and cash bonuses to significant privileges like travel rights. Many complied out of fear rather than loyalty, but only a handful successfully resisted the pressure to cooperate.

Ironically, the Stasi did not trust even its own personnel. Officers were monitored more strictly than any other group. Suspicions of disloyalty led to harsh consequences. The execution of officer Werner Teske in 1981 illustrated how merciless the organization was toward its own.

Indoctrinating the Young

By the 1980s, recruitment became more difficult as disillusionment spread. In response, the regime turned its attention to children and teenagers. Some as young as 12 were drafted into service as informants or future operatives. Targeting orphans and children from politically undesirable families allowed the Stasi to mold them without interference. This practice reflected the regime’s desperation as well as the depth of its commitment to controlling every aspect of society.

The Human Cost of Authoritarian Rule

The GDR prided itself on building socialism, but what it really built was a traumatized society. Alcoholism, mental illness, and high suicide rates plagued the population. Many lived in fear of surveillance and denunciation. Those who dared criticize the government faced dire consequences, while a small elite of party and Stasi officials enjoyed privileges far removed from the struggles of ordinary citizens.

The collapse of the regime reflected not only economic stagnation but also the population’s yearning for basic freedoms. Marx might have envisioned a world of equality, but in the GDR, people found only repression and empty promises.

The Wave of Change in Eastern Europe

The Stasi’s decline cannot be separated from the broader context of the 1980s. Across Eastern Europe, the Soviet grip was weakening. Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of openness and reform diminished the credibility of hardline rulers. When the Soviet Union announced that it would not intervene militarily in its satellite states, regimes that had relied on external force suddenly faced their people alone.

In East Germany, mass demonstrations, waves of refugees, and growing discontent made change inevitable. The largest protest, held on November 4, 1989, filled Alexanderplatz with hundreds of thousands who openly criticized the government on live television. Days later, a confused press conference by Politburo member Günther Schabowski led crowds to the Berlin Wall. When border guards failed to stop them, the wall collapsed, not by decree but by the will of the people.

Collapse and Dissolution

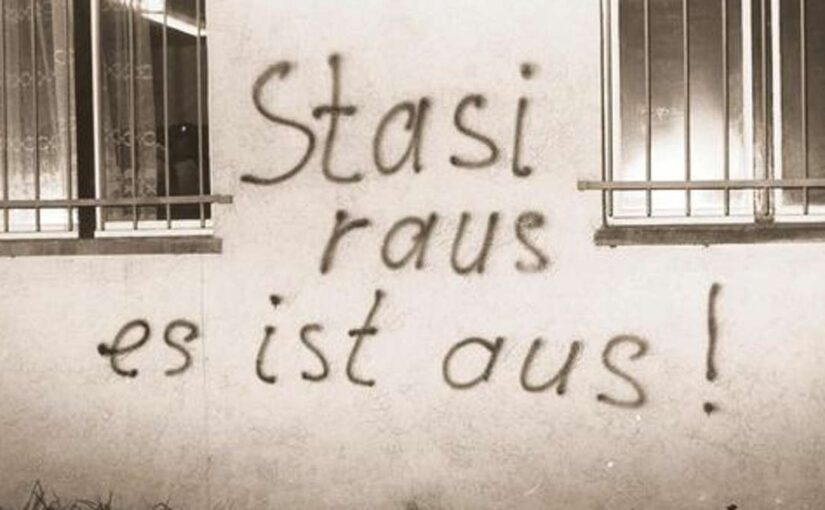

The fall of the wall marked the beginning of the end for the Stasi. Its authority disintegrated as quickly as the regime itself. Attempts to destroy evidence through shredding or burning files became chaotic and inconsistent. In December 1989 and January 1990, citizens occupied local Stasi offices, determined to preserve the truth of what had been done under their watchful eyes.

The final blow came on January 15, 1990, when tens of thousands of demonstrators stormed the Stasi headquarters in Berlin. Their fury reflected decades of repression. By February, the government formally ordered the dissolution of the Ministry for State Security. Within months, it ceased to exist.

Preserving the Memory

The story of the Stasi did not end entirely with its dissolution. Civil rights activists fought to preserve its archives, ensuring that the crimes, betrayals, and surveillance could not be erased from history. The archive now holds one of the most extensive collections of secret police documents anywhere in the world, amounting to over 100 kilometers of records.

These documents testify to the devastation caused by a regime that sought to control thoughts, words, and actions. They also stand as a warning to future generations about the dangers of unchecked surveillance and authoritarian power.

The Legacy of Fear

In hindsight, it is remarkable that the East German regime lasted as long as it did. The Stasi was effective at instilling fear, but it underestimated the human drive for freedom. No system of control, no matter how extensive, can suppress the longing for dignity forever.

The Stasi’s legacy is not only one of oppression but also of resistance. Citizens ultimately dismantled the very institution that had once seemed untouchable. The storming of Stasi offices in 1989 and 1990 remains a powerful symbol of people reclaiming their rights from a collapsing dictatorship.

Today, the archives stand as a monument to truth and justice. They remind us that while authoritarian regimes may rely on fear and control, their power is never absolute. In the end, it was the courage of ordinary people that brought one of the most formidable secret police systems in history to its knees.

Header image: Private archive of Reinhard Wenzel/BStU Source: Unknown.

If Teutonista has sparked your curiosity, deepened your appreciation for German history, or guided you through the joys of language learning, consider making a donation. Every contribution goes directly toward creating more original stories, accessible resources, and engaging insights that weave the ancient past into your everyday life.